On Boredom

Posted on 1st July, 2025

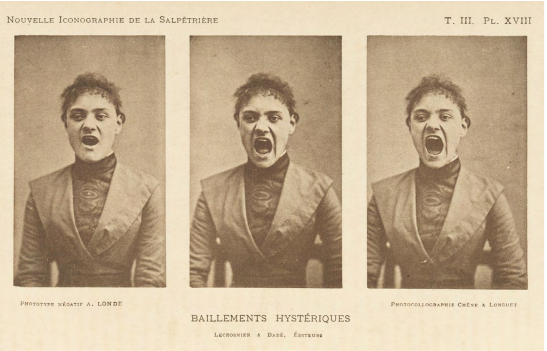

The Oxford English Dictionary defines boredom, tautologically, as ‘the state of being bored’, and provides us with two synonyms, perhaps by way of compensation: ‘tedium’ and ‘ennui’. The entry states that the first uses of the word ‘boredom’ in literature are found in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1852–3). The aptly named Lady Dedlock suffers from the ‘chronic malady of boredom’ because she is stuck in a marriage of convenience. Meanwhile, another character called Volumnia is described as someone ‘who cannot long continue silent without imminent peril of seizure by the dragon Boredom, [and who] soon indicates the approach of that monster with a series of undisguisable yawns’. Boredom, for the Dickens of Bleak House at least, seems to be a female malady, one that is by turn chronic, monstrous and spasmodic, a deadly sickness. Lady Dedlock was ‘bored to death’, he writes.1

That the OED’s lexicographers could find no better way of describing boredom than by resorting to tautology shows just how difficult the condition is to define. The word names the experience of a kind of deadlock, one that can be so obdurate and self-referential that the best way of accounting for it may be in its own terms: boredom means being bored. Failing this, one might resort to the use of synonyms – ‘tedium’, ‘ennui’, but also ‘monotony’, ‘dullness’, ‘dreariness’, ‘weariness’, ‘inertia’, ‘apathy’ and so on – knowing that none of these words means the same thing. The attempt to define boredom precisely may be a hopeless task. Yet it is at least arguable that this resistance to definition, and indeed this hopelessness, resonate in some ways with the experience of boredom, and so provide a true enough description of it. We are bored when we lose interest. The world then feels unavailable or withdrawn, refuses to mean anything other than itself, and appears to prevent us from relating to it in a creative or meaningful way. Described in this manner, boredom starts to sound like depression, even melancholia, though the condition is probably more mundane than either.

Much has changed since Dickens used the word, and it is often held that boredom, understood as a by-product of industrial capitalism, describes a structure of feeling that characterised Britain and Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, not what is now variously called postmodernity, late capitalism or the contemporary. Flaubert was bored, Emma Bovary was bored, Manet’s Olympia was bored, Lady Dedlock was bored, Volumnia was bored, the bourgeoisie was bored, Heidegger, Kierkegaard and Schopenhauer were bored, Nietzsche even thought that, after the seventh day of creation, God was bored, but we today are not bored. We are distracted, unable to maintain our attention for any considerable length of time, and this, it is claimed, prevents us from developing genuine and profound interests and from experiencing life authentically. This attention deficit, itself one of the most prevalent diagnoses in mental health today, especially of children, may also make us vulnerable to manipulation and exploitation. Our perception of the world is so fragmented and overloaded by new technologies that we risk losing our critical faculties altogether, even, according to one critic, our capacity for sleep.2 Meanwhile, hundreds of books are published each year that show us how to focus our minds, how to respond with greater ease to the proliferation of information in what has been called ‘the age of distraction’.3 The implication is that the ‘age of boredom’,4 as Flaubert described it, has now passed. The principal culprits are thought to be the culture industries and, more recently, the internet, together with the digital technologies that allow us to access it. Under such conditions, it would seem that the time needed to be bored is no longer available. We may now even feel nostalgic for those times in our lives when we were bored: in childhood, say, when time seemed to slow down, sometimes painfully so. The danger in this form of retrospection, of course, is that boredom is idealised or romanticised. ‘Boredom is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience,’ wrote Walter Benjamin. ‘A rustling in the leaves drives him away.’5 Boredom may at times be a dream bird, the ground of creativity, and so quite unlike Dickens’s dragon or monster. Yet it should not be forgotten that, if the rustle of leaves distracts us from what may be the deeper and more fundamental experience of boredom, and if distraction, once a remedy or palliative, has since become its own sickness, then boredom nonetheless remains an experience that we spend much of our lives trying to avoid, and for good reason. Being bored is a little like being dead – in a minor key. ‘Concert, assembly, opera, theatre, drive, nothing is new to my Lady under the worn-out heavens,’ writes Dickens of Lady Dedlock.

On Boredom addresses boredom in its manifold and uncertain reality, and asks what might be at stake in thinking about the affect today. One of the basic questions the writing and art included in this volume pose is whether there is a creative or critical potential to boredom or whether it is in fact as deadening an experience as it is often held to be. ‘All boredom is counter revolutionary,’ cried the Situationists in the 1960s. Perhaps that is so. But perpetual revolution can itself become boring, permanent change can feel like sameness, and what is striking is how boredom, itself an ordinary, everyday experience, can become the site of some of our most extreme fantasies and projections: of revolution, counter-revolution, sickness, deadness, creativity, dream birds, dragons and monsters. Why might this be so? Is boredom really such a Pandora’s box? Or do these fantasies betray just how anxious we are at the possibility of confronting our own boredom, with the risk that we might encounter a meaningless kernel at the very heart of what we call life?

About the Authors

This is an excerpt from the open access book On Boredom, edited by Susan Morris and Rye Dag Holmboe (UCL Press).

Susan Morris is an artist interested in the relation between automatic drawing, writing and photography. She uses various media including chalk on paper, inkjet printing and Jacquard tapestry. Works are often generated directly from recordings of data such as her sleep/wake patterns (using a scientific-medical device called an Actiwatch) or her unconscious bodily movements as recorded in a motion capture studio. Recent essay writing includes ‘Drawing in the Dark’ for Tate Papers No. 18, 2012, and ‘A Day’s Work’, catalogue essay for the exhibition for A Day’s Work that Morris curated for SKK, Soest, Germany, 2019.

Rye Dag Holmboe is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at UEA, where his research examines the relationship between creative process and psychoanalysis. He completed his PhD at UCL in 2015 where he was an AHRC Doctoral Scholar. Holmboe has published books on contemporary artists as well as articles on art, literature and theory. His book on Sol LeWitt will be published by MIT Press in 2021 and he is currently writing a monograph on Howard Hodgkin, which is supported by the Howard Hodgkin Legacy Trust. He is also in the third year of training at the British Psychoanalytic Association.