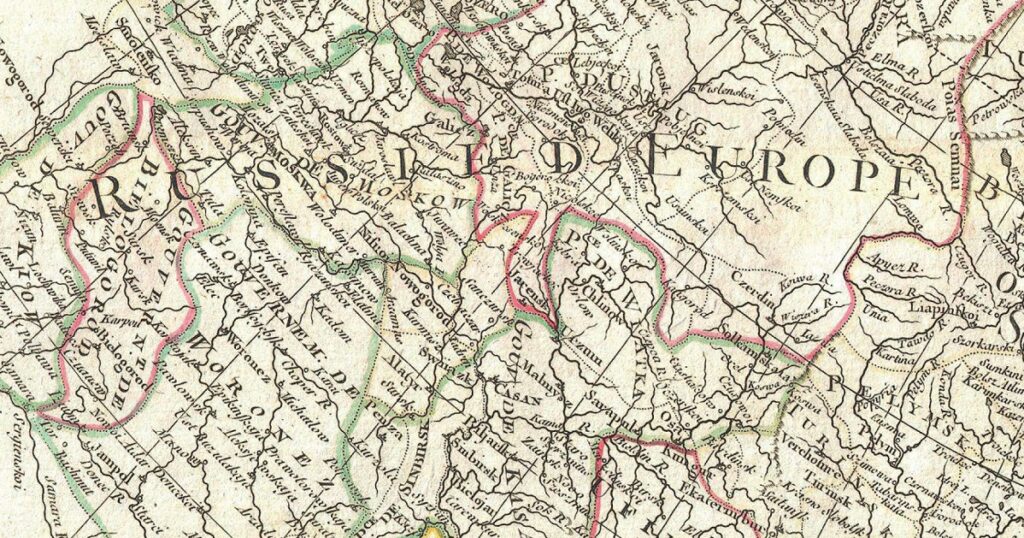

Mapping Russia in the shadow of Peter the Great

Posted on 8th October, 2024

To mark the publication today of the late Denis J. B. Shaw’s Reconnoitring Russia: Mapping, exploring and describing early modern Russia, 1613-1825, we bring you an excerpt from the Introduction. This passage provides the historical context for the book’s overall goal of explaining how Russia’s rulers and its educated public came to know and understand the territory of their expanding state and empire.

‘I love my country in the way that Peter the Great taught me to love it.’

Petr Chaadaev, 1837

This book is about how the Russians came to know Russia. It focuses on ‘those practices – observing, mapping, collecting, comparing, writing, sketching, classifying, reading, and so on – through which people came to know the world’ (Withers 2007, 12). More precisely, it concerns those geographical practices through which the territory of the Russian state and empire, and to a lesser degree the rest of the globe, became known to the country’s rulers and its educated public.

As intimated by the epigraph to this chapter, a key moment for this book is the reign of Peter the Great (1682–1725). The noted Russian writer and philosopher Petr Chaadaev regarded Peter’s reign as a turning point in the history of his country, a time when Russia threw off the shackles of its medieval past and adopted a new, more progressive role, one open to the influences of the outside world, and of Europe and the West in particular (Kohn 1962, 50–1). Writing in 1837, Chaadaev declaimed:

‘One hundred and fifty years ago the greatest of our kings – the one who supposedly began a new era, and to whom, it is said, we owe our greatness, our glory, and all the goods which we own today – disavowed the old Russia in the face of the whole world. He swept away all our institutions with his powerful breath; he dug an abyss between our past and our present, and into it he threw pell-mell all our traditions. He himself went to the Occidental countries and made himself the smallest of men, and he came back to us so much the greater; he prostrated himself before the Occident, and he arose as our master and our ruler. He introduced Occidental idioms into our language; he called his new capital by an Occidental name; he rejected his hereditary title and took an Occidental title; finally, he almost gave up his own name, and more than once he signed his sovereign decrees with an Occidental name.’

Chaadaev’s contemporaries and subsequent writers engaged in heated debates about whether Peter’s policies had had positive or negative consequences for Russia’s long-term development. In the present book I shall adopt a more nuanced stance on Peter’s reign than that taken by Chaadaev, but I do agree with him that the reign represented a significant break with the past. The book will focus on geographical practices, or what I shall call geographical endeavour, over the period between 1613, when the Romanov dynasty assumed power (but with some attention paid to the preceding era) and 1825, the conclusion of Alexander I’s reign, or what is often termed the end of Russia’s ‘long eighteenth century’. Hence it will focus on the period between the inauguration of the dynasty to which Peter belonged and end at the point immediately before the onset of the precipitate changes that characterized the nineteenth century – the building of the railways, the Emancipation of the Serfs (1861) and the initial industrialization and urbanization of Russia. Chronologically, Peter’s reign is thus the period around which the book pivots.

Chaadaev’s emphasis on the significance of Peter the Great’s reign points to a central feature of the book – the comparative dimension. Peter’s reforms derived from his admiration of a series of Western developments, and these he strove to emulate in Russia, adapting them to the very different circumstances prevailing in his homeland. We cannot understand Russian geographical endeavour from Peter’s time (and even to a limited extent before Peter) without placing it in a broader European context. Throughout the book, therefore, explicit reference is made to this broader context.

The principal question to be addressed in this book is: by what means did Russian geographical endeavour reveal and explain to Russians the variable character of the territories which formed their expanding realm? Related questions include: how far did Russian geographical endeavour inform Russians of the character of the globe as a whole, and to what extent was Russian geographical endeavour distinctive? Finally: how far did Russian geographical endeavour inform Europeans of the nature of Russian territory and of Russia’s place in the world? Of course, I am aware that these questions are far too broad to tackle in a single volume, but I do at least hope to build on earlier work relating to such themes and to open up new questions for future research.

Whilst the book will consider many different types of geographical endeavour over the period, I make no pretence to be systematic or comprehensive. That would be impossible in a volume of such length. Rather, in aiming to provide a general framework for understanding the nature of geographical endeavour, and describing how it changed through time, I particularly emphasize scholarship and episodes that appear to me to be especially significant. No doubt my choice will disappoint or displease some readers. But by seeking to place selected aspects of the Russian story into an international context I hope to show how far that story was distinctive and how far Russia’s experience was just part and parcel of a common endeavour in the early modern period.

About the Author

This is an excerpt from Reconnoitring Russia: Mapping, exploring and describing early modern Russia, 1613-1825 by Denis J. B. Shaw.

Until his death in March 2024 Denis J. B. Shaw was an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Birmingham, where he had formerly been Reader in Russian Geography.